Introduction

Putting Economics of Mutuality into practice involves adopting a new type of business model and requires a new type of management practice that puts much greater emphasis on certain non-financial performance indicators in the categories of human, social, and natural capital. It also requires these non-financial indicators to be linked strongly to financial performance indicators in the company’s system for performance measurement, performance management, and, ultimately, compensation.

Traditionally, the backbone of the performance measurement and performance management in business is financial accounting, and the primary success indicator is financial profit as it appears in the profit and loss statement (P&L). To effectively support the transformation of the business from one main dimension (financial) to multiple dimensions (financial, human, social, and natural) we need to challenge our traditional ways of constructing and measuring profit and explore ways of transforming the financial P&L into a mutual P&L.

The mutual P&L will be a powerful force for change to help put the Economics of Mutuality (EoM) into practice, by:

Signalling clearly to the organization that performance in terms of human, social, and natural capital impacts is at the same level of importance as financial performance

Ensuring rigorous performance management in non-financial dimensions (e.g. robustness of metrics, frequency of review, and decisions to drive performance)

Creating a stronger alignment in the organization between purpose and the management system (including, ideally, the incentive system).

Conceptual Framework

To create a mutual P&L framework, we need first to understand some fundamental conceptual differences that exist between financial accounting and the measurement of human, social, and natural capitals. For simplicity we can focus on the three most important issues:

Internality and externality: Financial accounting is focused on elements (equity, assets, liabilities, income, and expenses) that belong to the reporting entity based on legal or contractual rights and obligations (in that sense, considered ‘internal’ to the company). However, a company often mobilizes (and affects) the human, social, and natural capitals of its ecosystem in a way that is not limited to legal or contractual rights and obligations (thus considered ‘externalities’). For example, a business may cause damage to environmental assets that it does not own, without having any legal obligation to pay a compensation for it. This type of externality would be ‘internalized’ in the mutual P&L.

Exhaustivity: Financial accounting must be exhaustive in all material aspects to be considered exact. Failing to recognize a significant income or expense is in no way acceptable in the construction of the financial P&L. In contrast, human, social, and natural capitals, by nature, may have multiple and subjective dimensions, with potentially complex interdependencies between them. Therefore, it does not appear realistic to define exhaustively the externalities of a given company. The mutual P&L will take into account the externalities selectively, and not exhaustively.

Monetary value: All elements in financial accounting are captured in terms of monetary value. In many cases it is a challenge to evaluate or describe human, social, and natural capital issues in terms of monetary value (e.g. the dollar value of well-being at work and employee training, the direct and indirect cost implications of plastic in the oceans, and the cost of child labour in the supply chain). It is important to keep in mind that not all elements of human, social, and natural capitals can be (nor should be) ‘monetized’ and the process of translating a non-financial externality into a dollar value is simply necessary to create a connection with the concept of profit in the mutual P&L. Arguably, the basis for valuation in this case will be the valuation ‘at cost’ because it does not require making any assumption on a ‘market value’ or intrinsic value of the non-financial capitals.

These considerations are important to develop a concept of mutual P&L that is both technically feasible and meaningful. Because of them, we cannot entertain the idea of an all-inclusive accounting framework that would capture all elements of human, social, and natural capital used in a given business and show the dollar value of their stock and flow. These limitations lead us to approach the concept of mutual P&L as follows: the mutual P&L is an extension of the financial P&L that takes into account selected human, social, and environmental issues that are relevant for the organization and its ecosystem, towards a stated purpose.

The idea of extending the financial P&L comes from the fact that the P&L is a cornerstone of a company’s operating system and yet is incomplete from the standpoint of EoM. The financial P&L does not reflect any of the deep interactions that exist between the company and the human, social, and natural capitals present in its ecosystem— although these interactions are often essential to the achievement of the purpose, or simply to the sustainability of the company over time.

By analogy with financial capital, we can think of these interactions in terms of capital usage (i.e. consumption and depreciation) or capital creation (i.e. appreciation). For instance, a company that employs large amounts of a certain form of human capital depends on that human capital. If this company, as the result of its operations, has a positive impact (‘pay back’ or ‘dividends’) on the human capital present in its ecosystem, it improves its own prospects of prosperity. Conversely, if this business has a negative impact on the human capital as a result of its operations, it is limiting its own potential of further profitable growth. This is the type of impact (positive or negative) that we want to capture in the mutual P&L—to the extent that it is relevant and significant to the organization’s purpose and strategy.

Schematically, to transform the P&L into a management tool that is effectively aligned to a company that has purpose and supports the implementation of EoM, it is necessary to include in its scope (in a meaningful and practical manner) the impact of the business on not only one form of capital (financial) but multiple forms of capital, as shown in Figure 14.1.

Constructing the Mutual P&L

The construction of the mutual P&L requires four distinct phases that are discussed below. The first phase is to select the right issues to be taken into account in the mutual P&L. The second phase is to ensure that each issue is clearly defined and has adequate performance measurement and management. The third phase is about translating the non-financial impacts into P&L entries with a dollar value. The final phase is about integration and presentation of the mutual P&L.

Phase 1: Selection of Material Issues

The fact that human, social, and natural capital issues by essence cannot be apprehended exhaustively will lead the organization to select a limited number of material issues that are most relevant and significant to the achievement of its purpose, with its ecosystem and the idea of mutuality in mind. This selection process is the result of the ecosystem-mapping and the pain-point analysis as discussed in Chapters 6 and 7.

The number of material issues to be considered for the mutual P&L needs to be carefully calibrated to have the right balance between coverage and focus. Focusing the organization on a small number of issues can drive better performance, increase the clarity of the mutual P&L, and keep the process from becoming a burdensome bureaucratic exercise. Trying to cover too many issues could result in resource dispersion, unclear performance assessment, and excessive paperwork. The selection of top issues is a phase where the involvement and judgement of the organization’s leadership is of paramount importance. The selected issues need to be truly and deeply connected to the purpose and strategy of the business and, as such, stay relevant in the medium or long term. On this condition, the mutual P&L will be stable in its construction and comparable across the years.

Which human, social, and natural capital issues are material is a function of a company’s industry and strategy. For example, carbon emissions are material for an electric utility company but not for a pharmaceutical company where access to medicine is. Stakeholder engagement is a key element in determining a company’s material issues. General guidance, with an emphasis on externalities, is available from Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), and industry-specific guidance with an emphasis on what is of interest to investors is available from the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB).

Phase 2: Business Initiatives, Performance Measurement and Management

The human, social, and environmental issues that are selected in Phase 1 are critical to the organization’s purpose, strategy, and business model. As such, they need to be monitored and managed with the same attention and rigour as the (more traditional) commercial or financial operations in the business. The organization will drive initiatives to address those issues and create the conditions to manage and measure performance for each of them:

Clear definition of the issue, the objective of the intervention, and the link to purpose

Defined resource allocation to meet the objective (budget)

Performance criteria (non-financial metrics as discussed in Chapters

9 to 12) and targets

Empowerment and responsibilities in the organization.

A precise articulation of these elements for each selected EoM issue is a condition to develop a mutual P&L that is credible and based on robust data, especially for resource allocation, metrics, and their targets. At this point, it is necessary to make a distinction between two types of priority issues that may arise from the pain-point analysis:

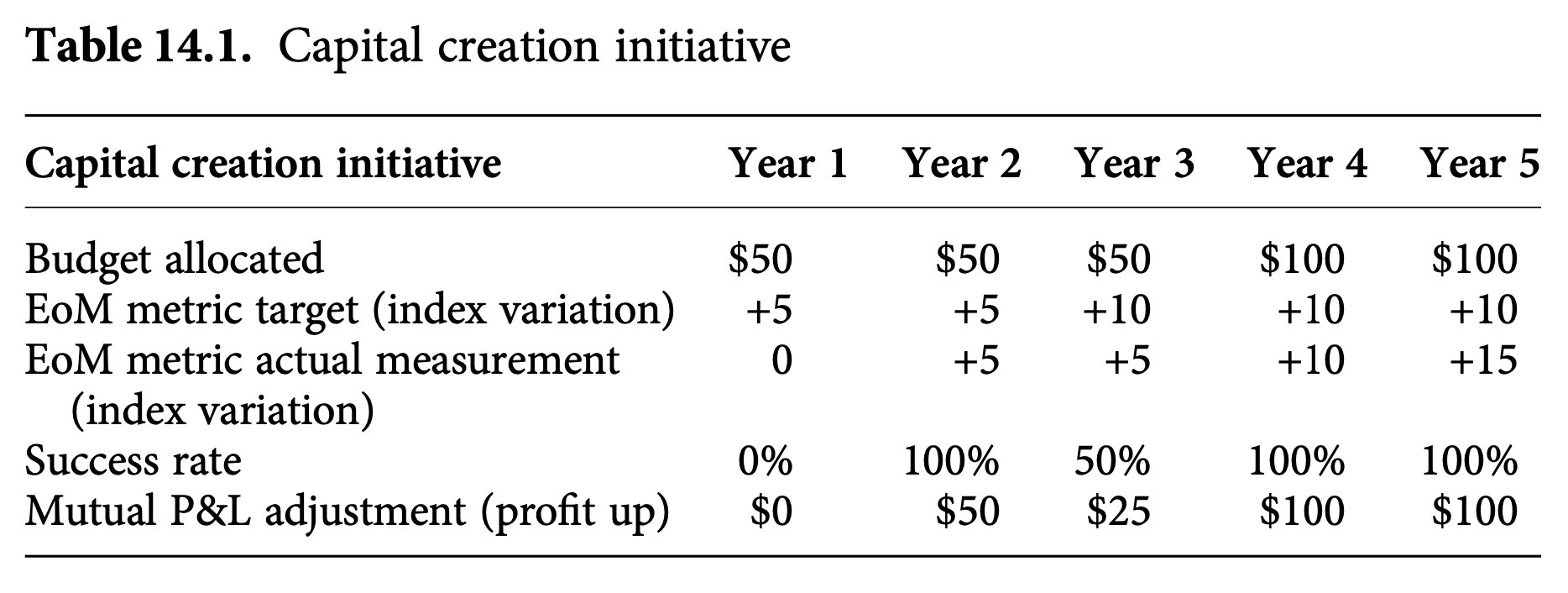

Capital creation initiatives: When the company identifies a critical pain point in the ecosystem that is not resulting from its own operations, but can be positively addressed by it with mutuality in mind (i.e. with a shared benefit for the company and its ecosystem). For this type of situation, it is necessary to have a clear measurement of the resources allocated (budget) and whether the initiative is effective in addressing the external pain points (metrics showing actual impact vs. targets).

Capital depletion issues: When in the ordinary course of business the organization has a negative impact on the human, social, or natural capitals causing a threat to the ecosystem and ultimately the achievement of its purpose. The issue is not visible in the financial P&L because the company is not paying for it. Typically, this would be the type of issue facing a company that depends on the massive consumption of a scarce natural resource or causing a form of pollution that has substantial negative externalities. For this type of situation, it is necessary to measure the (negative) impact and to create an incentive to find a remedy (at least to stop the negative impact or to repair the consequences).

Phase 3: Valuation of Impacts

As we mentioned earlier, items need to be expressed in terms of monetary value to be included in a P&L. At first glance, this poses a problem as human, social, and environmental issues are difficult to value in monetary terms. However, in accounting there are various valuation methods and the one that can apply to the issues defined in Phase 2 is the valuation at cost. With this method, it is not necessary to make an assumption on the intrinsic value of the human, social, or natural capital at stake (depleted or created). We can translate these issues into accounting language by focusing on the cost implication for the company.

1. For capital creation initiatives: treat the spend as investment, not expense

When a business initiative results in the creation (or positive reinforcement) of human, social, and natural capitals that are external to the company but crucial to its strategy and its ecosystem, the resources allocated to that initiative are considered as an investment and not as an operating expense in the mutual P&L. The P&L adjustment in this case is an increase of the profit shown in the P&L.

Conceptually, this consists of recognizing that the human, social, or natural capital creation is similar to the creation of an asset that— although it is not owned by the company in this case—will contribute to the company’s profitable growth in the future. By way of analogy, the logic is similar to the treatment of internal software development costs, that can be capitalized both in US GAAP and IFRS if certain criteria are met.

One important idea is that the spend should be considered an investment only on the condition that the initiative has an actual impact on the external capitals, that can be measured and considered successful. Due to the particular essence of human, social, and natural capitals, the measurement of impact relies on the specific set of metrics developed for EoM (Chapters 9 to 12) and the criteria for success is the achievement of pre-defined targets for these metrics. Without these criteria (defined in Phase 2), the mutual P&L would lack the necessary robustness and credibility.

Treating the expenditure as an investment and not an operating cost can be a powerful enabler to build an EoM business model because it removes the conflict that often exists between, on one hand, the need to allocate resource in line with the company’s long-term purpose or strategy (which is typically defined over a medium to long-term horizon), and, on the other hand, the need to deliver the short-term profit target (as measured in the P&L). Changing the accounting treatment does not change the fact that the money is spent as a matter of fact (in cash). However, the access to budget will be generally easier if the spending does not have a full immediate negative impact on the profit measurement, and the decision can be made with the long term in mind (as it is the case typically for fixed assets investment budgets).

Table 14.1 gives an illustration of an initiative with different levels of success (actual impact vs. targets) across the years, as measured by EoM metrics. The spend is considered an investment only to the extent that it drives effective results, in line with a pre-defined target. When the spend does not entail successful results, it is considered an operating cost (following the same logic as the write-off of an asset that has no value).

2. For capital depletion issues: internalize hypothetical replenishment costs

The company measures the capital depletion using the appropriate non-financial metrics (Chapters 9 to 12), then identifies a hypothetical replenishment cost corresponding to the investment (in dollar terms) that would be necessary for the company to replace the depleted capital. This requires it to analyse the options available to replenish the capital in the specific context of the business (location, access to resources and technology, etc.), understand the cost of these options, and retain the one that would be preferred by the company (in terms of practicality and affordability).

The impact of internalizing the hypothetical cost in the P&L is a decrease of profit shown in that P&L. The cost of replenishing the external capitals is hypothetical as long as the company does not actually spend it (in which case the cost will be already included in the financial P&L). There are many reasons why companies don’t spend this money in the first place including lack of legal obligation, lack of awareness, lack of social and environmental responsibility, lack of long-term thinking, and lack of resources. By internalizing into the P&L the hypothetical replenishment costs related to material capital depletion issues, the leaders of an organization can change its context in a profound way as they:

Create awareness, make the issues highly visible internally so they can be managed

Create an incentive for the organization to mitigate or solve the issues (drive change)

Better understand what part of the financial profit is sustainable over the long term and what part of the profit is being generated in the short term at the expense of the future.

Table 14.2 gives an illustration in the case of a company that measures a capital depletion issue consistently over time and creates a situation where the P&L will evolve positively when the issue is addressed or mitigated (years 4 and 5).

Phase 4: Integration and Presentation of the Mutual P&L

The P&L adjustments determined in Phase 3 can complement and modify the financial P&L to form the mutual P&L as shown in Table 14.3 below.

By taking into account selected non-financial material issues as explained above, the mutual P&L becomes a management tool that is not dramatically different from the traditional financial accounting, but sufficiently different to tell a different story about a company’s profit performance and drive different decisions and actions.

The mutual P&L does not replace, nor challenge, traditional financial reporting because it serves a different objective. External financial reporting ‘provides financial information about the reporting entity that is useful to existing and potential investors, lenders, and other creditors in making decisions about providing resources to the entity’ (definition from the IFRS Conceptual Framework). The mutual P&L is a new form of internal management accounts that provides information that is distinct and additional to the external financial reporting for the organization itself to drive performance toward its purpose and with EoM in mind. The above table shows that the two sets of accounts, although different, can always be reconciled easily.

Conclusion

To be meaningful and effective, the mutual P&L relies on the right selection of material issues and initiatives, the right metrics, and a certain degree of stability over time. The mutual P&L will be a powerful tool to drive change if the mutual profit becomes the basis of financial incentives for the organization’s leadership and staff, in place of the traditional financial profit.

While we believe this to be a promising idea, we are also well aware of the challenges in implementing and achieving the benefits of a mutual P&L. The measurement issues are obvious and have been discussed. These technical issues, while difficult, are the easiest to resolve. Much harder are the organizational ones, such as the issue of how the different ‘realities’ of the financial and mutual P&L will co-exist. Will one become dominant or will each be used for its intended different purpose? For the mutual P&L to be successful in contributing to the company’s purpose, senior management needs to clearly explain its purpose. Senior management needs to hear and respond to concerns raised by those implementing it. Everyone needs to recognize that the mutual P&L is a new idea whose proof in practice remains to be seen. Its success will depend on an appreciation of this fact and the goodwill of everyone involved.

Finally, this chapter focuses on the mutual P&L and does not discuss the notion of a mutual balance sheet. This is the result of a conscious choice. Indeed, the P&L describes flows, operations, and their impact in terms of net value creation over a period of time, and is the primary measurement of business performance in a majority of companies. Proposing a different mode of P&L construction supporting the EoM principles will achieve the maximum impact in terms of changing decisions and actions with the minimum complexity. A condition, though, is to always consider the P&L with the long-term in mind (i.e. the history of P&L over multiple years as shown in the illustrative tables above). Conversely, the construction of a mutual balance sheet raises a number of problematic technical questions (e.g. the notion of hypothetical assets and liabilities, risk of confusion between hypothetical and real liabilities, amortization of capitalized costs, opening balance sheet, etc.) with little or no additional benefits, in the sense that in most industries’ management decisions are much more driven by the financial P&L than the financial balance sheet.

For this reason, we believe that, for now, the concept of mutual P&L (with no need of a mutual balance sheet) will be the most powerful and accessible tool to help guide a company to achieve its purpose in a profitable way over the long term through the resource allocation decisions made by management. Accomplishing this will require the implementation of the mutual P&L throughout the entire organization and at every level where P&Ls are currently being produced.

Robert G. Eccles is a former tenured professor at Harvard Business School and is now a visiting professor of management practice at Saïd Business School, Oxford University. He is the founding chairman of the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, an advisor to the Impact Management Project, and a member of the board of directors of the Mistra Center for Sustainable Markets at the Stockholm School of Economics. Eccles is a ‘capital market activist’ dedicated to ensuring that the capital markets support sustainable development through such mechanisms as integrated reporting. He is also a dedicated weight-lifter.

François Laurent is a senior Catalyst fellow based in Paris who holds a master’s degree in business administration (EDHEC, France). He spent seven years in audit and consulting in Europe and Africa before becoming a finance director at Mars and Wrigley for eighteen years in a wide variety of geographic locations. As a former regional finance vice president in the Middle East, Central and Eastern Europe, Western Europe, and Asia-Pacific, Francois has acquired unique experience of managing and developing business in diverse market situations and cultural environments. He also has extensive experience in international accounting standards, financial reporting and audit.

Accounting for Natural Capital

By Richard Barker

The Impact of Mutual Profit on Business Behaviour

By Robert Eccles and Judith C. Stroehle

Published by Oxford University Press. Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom.

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark ofOxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Oxford University Press 2021. The moral rights of the author have been asserted. First Edition published in 2021. Impression: 1.

Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization.

This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of this licence should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication. DataData available. Library of Congress Control Number: 0000000000. ISBN 978–0–19–887070–8. DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198870708.001.0001.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.