Introduction

It is clear...that Mars, Incorporated is exploring the path to becoming a long-run investor in a holistic business future as opposed to a short-sighted, profit-only driven entity.

Mars External Peer Review Panel, July 2013

The roots of the Economics of Mutuality (EoM) management innovation can be found deeply embedded in the DNA of Mars, Incorporated—a global food and beverage company whose origins date to 1911, when founder Frank Mars, Snr. began selling butter creams from his kitchen in Tacoma, Washington. The Mars-O-Bar company was launched in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1922, and relocated to Chicago in 1929, shortly before the start of the Great Depression. In 1932, Frank’s son Forrest left his father’s company under the condition that any business he set up would be outside the United States. With $50,000 and the family’s candy formulas, he moved to England to start his own Mars chocolate business in the industrial town of Slough, with a dream to build a business based on the objective of promoting ‘a mutuality of service and benefits’ for all stakeholders.

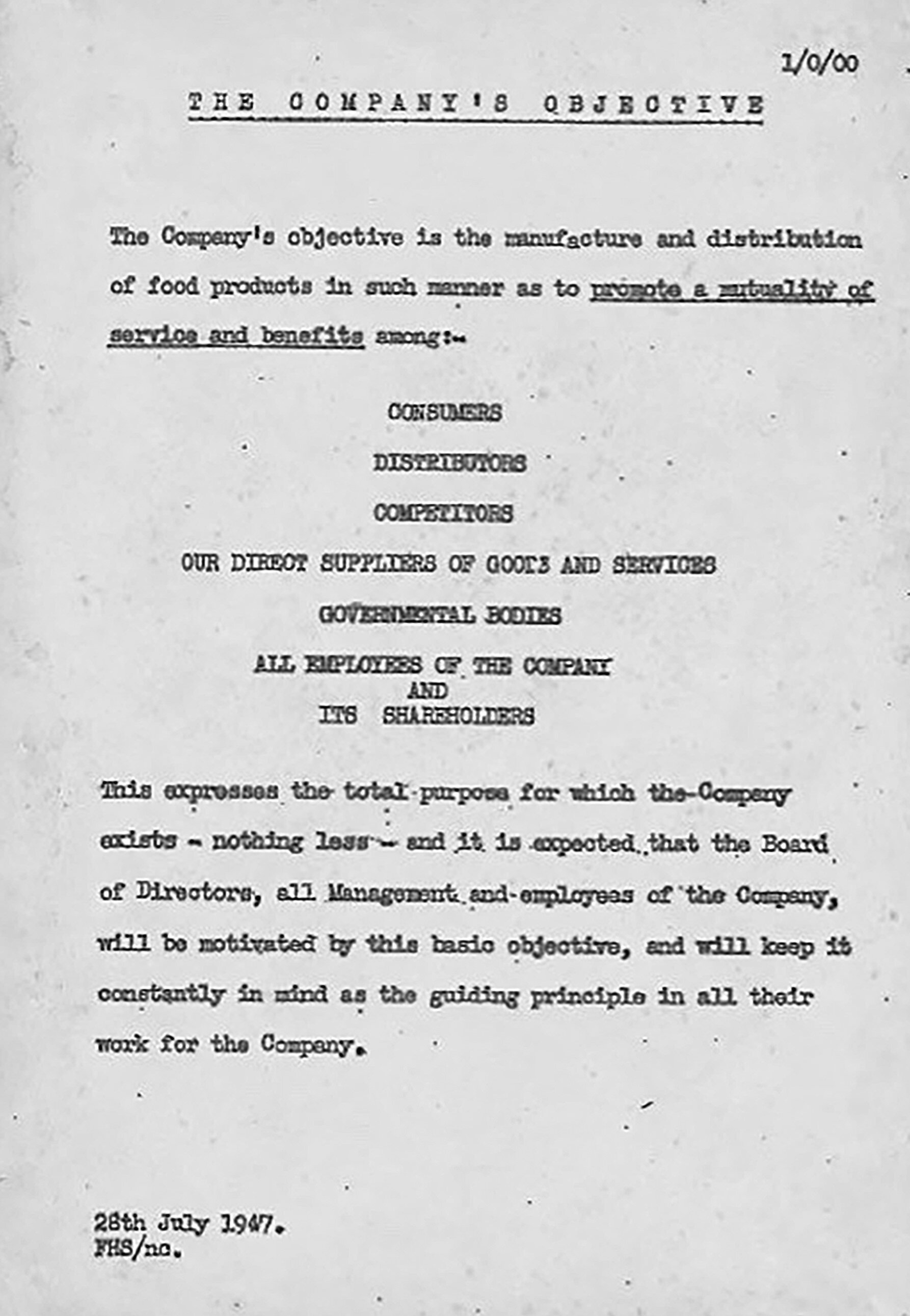

Forrest’s ‘mutuality of benefits’ approach to business was later codified in a Mars personnel manual that he drafted,1 and in his 1947 letter titled, ‘The Company’s Objective’ (Figure 4.1).2 This approach was more formally expressed in 1982 by his heirs as the ‘Mutuality Principle’—one of five core operating principles of Mars along with quality, responsibility, efficiency, and freedom—that remain in effect today.3

Mars has now grown into one of the world’s largest and most successful corporations, operating in more than eighty countries across 420 sites. It employs over 100,000 ‘associates’,4 has over one hundred factories, and generates in excess of $35 billion in annual revenues across five business segments. These cover petcare, confectionery, food, and an entrepreneurial unit established in 2018 called Mars Edge that is exploring new opportunities at the nexus of data and nutrition.

Figure 4.1. ‘The Company’s Objective’: 1947 letter from Forrest Mars, Snr. Source: Mars family archive.

The Future Mars Laboratory for EoM: Catalyst Think Tank

In the 1960s, Forrest Mars personally established an internal think tank for his company to challenge orthodox business thinking. This unit, Catalyst, currently led by the Mars chief economist, continues to have a purpose closely aligned with Forrest’s intuition that ‘management is about applying mathematics to economic problems.’5

The Economics of Mutuality programme, launched by Catalyst at the start of 2007 after preliminary research begun in late 2006, is the most expansive example of Forrest, Snr.’s vision of the role of management science in business. A much earlier illustration dates to the 1970s when Catalyst addressed what was then a major challenge for Mars of commodity procurement involving the cocoa supply. Catalyst helped the business by introducing weather and climate data into the existing crop yield’s forecasting models to improve the accuracy of the predictions, thereby providing a better risk assessment against market fluctuations. This was very new for the business at the time.

This early work on cocoa led Catalyst into other quantitative disciplines, such as statistics, times series analysis, econometrics, and data mining that, in turn, gave birth to robust metrics for what had previously been thought to be unmeasurable—the impact of marketing on sales. The advertising evaluative approach Catalyst pioneered yielded a doubling of the efficiency of Mars advertising, bringing huge savings and giving the company advanced capabilities that competitors of Mars continue to try to replicate.

The EoM Journey Starts with an Unusual Shareholder Question

What should be the right level of profit for Mars?

John Mars, shareholder—question posed to Mars CEO & CFO in late 2006

The EoM journey at Mars can be traced back to a conversation in late 2006 between John Mars (son of Forrest), then Mars CEO Paul Michaels, and then CFO Olivier Goudet, during which John asked what the right level of profit should be for the company. This was a remarkable question coming from a shareholder, as most would define the ‘right’ level of profit as the maximum that can be extracted from a value chain to ensure continued growth, and for distribution as shareholder dividends.

But far from implying that the Mars family shareholders demanded higher profits, John Mars in 2006 was troubled that the company’s profits might be too high. He was concerned that if the firm extracted more than its right from its value chain partners, this could create a squeezing effect whereby one stakeholder would be driven to squeeze another for more margin, and so on, ultimately creating a disequilibrium that would disadvantage Mars. As he explained to the co-chairman of the Mars Science Advisory Council (who later led two external peer reviews of the EoM programme), ‘If you take care of the left [downstream] part of the value chain [growers, processors, etc.], it will take care of the right [upstream] part of the value chain [manufacturers, distributors, consumers].’6

This profit question was delegated by the Mars leadership team to the Catalyst think tank, thereby opening the door for the EoM programme, which started with the broadly accepted premise that businesses only manage what they measure. Therefore, Catalyst hypothesized that the question of the ‘right level of profit’ must address management incentives because incentives largely govern the behaviour of managers.7 And to do this properly, an examination of what is of value to business and can be used by business to create more value—beyond just monetary profits (financial capital)—would be necessary. This, in turn, led to the development of non-traditional (for business) metrics to account—in ways that were simple enough for business managers to use, stable across markets, and robust scientifically—for the value of non-monetized forms of capital for people (human and social capital) and the planet (natural capital).8

Back to the Future: Sowing the Seeds for EoM in the Mars DNA

The impact of founders’ beliefs, values, and assumptions is the most important source of an organization’s culture, which does not form spontaneously or accidentally.9

Professor Edgar Schein, MIT

While the story of EoM at Mars began with the question about the right level of profit, the mutuality approach to business that provided such fertile ground for these principles to emerge was fostered by John’s father, Forrest.

The culture that Forrest, Snr. modelled, and that was carried forward by his offspring and now by their own children, was characterized not only by mutuality, but also by a long-term perspective; continuous shareholder reinvestment back into the company; patience; risk tolerance; and a willingness to fund a unit (Catalyst) for half a century and counting to continue to challenge the status quo inside the firm.

In his 1947 letter, ‘The Company’s Objective’, it is notable that Forrest reversed the typical order of precedence that in most corporations puts the interests of the shareholders foremost, sometimes mentioning the consumers, but often leaving out many other key stakeholders without whom the company would be unable to operate. By contrast, Forrest put shareholders (himself alone in 1947) last, with even competitors placed above himself in order of precedence. Specifically, his letter stated:

The company’s objective is the manufacture and distribution of food products in such a manner as to promote a mutuality of services and benefits among: consumers, distributors, competitors, our direct suppliers of goods and services, governmental bodies, all employees of the company and its shareholders.10

The substance of this letter reflected Forrest’s personal business values. These values were very likely to have been influenced by his experiences learning the chocolate business in the United Kingdom of the Great Depression era. He would have had the opportunity to observe the practices of a particular sub-set of family-owned confectionery firms, of which seven of the ten largest were owned by practising Quakers.11

Of these, the best known are Cadbury’s and Rowntree’s, whose businesses were influenced at every level by their beliefs. Cocoa and drinking chocolate were produced as alternatives to alcohol, which was viewed as among the causes of poverty and deprivation. Both George Cadbury and Joseph Rowntree were known for their honesty and paternalistic way of caring for their workforce, and the ethical way in which they conducted their businesses. As the Rowntree Trust explains, ‘Quakers didn’t wring every penny out of a business.’

Mars was and remains a strictly secular company, yet some of the more socially oriented approaches to business of his early chocolate competitors to which Forrest was exposed in the 1930s almost certainly resonated with him as ‘good business sense’. This would have been further reinforced by the unarguable financial success of such competitor UK firms, even during this time of severe economic downturn, making it logical for Forrest to infuse his own company’s culture with his personal morals and ethics, which in his case included mutuality.

Forrest’s ideas may also seem to have something in common with the ‘cooperative’ and ‘mutual’ businesses that emerged in the United Kingdom in the nineteenth century. There is a similar emphasis on long-term relationships and on sharing benefits and services amongst a range of stakeholders in such firms. However, it is important to understand that in these companies mutuality refers to ownership and governance. Cooperatives developed as groups of workers, or small shopkeepers decided to work together and pool resources. Effectively, each member contributes equity capital and shares in the control of the firm. A so-called mutual is more usually a financial organization (building society or life assurance firm) owned by its clients or policyholders— in other words, customers. In a widely cited 1991 paper on mutuals, the economist John Kay describes different types of firms in terms of the way they prioritize stakeholders when distributing the added value earned from their activities: ‘An employee-controlled organization will . . . seek to create added value, but will then distribute it primarily among workers. In the agricultural sector we often observe supplier cooperatives, which return the added value which they create to that group of stakeholders. A mutual organization stresses the claims of its customers in the distribution of added value.’ So, while the absence of external shareholders may make it easier for what are traditionally known as mutuals to practise mutuality as it is understood by Mars, the two concepts are not the same.

The family-owned nature of Mars in the United Kingdom and the United States during the challenging economic times of the 1930s—with Forrest’s notably frugal way of living, investing much of his ownership dividend back into the business year after year—gave greater flexibility to manage for the long term than publicly traded companies. The latter, for example, faced intense shareholder pressure to deliver returns on a short-term quarterly basis. Forrest’s long-term orientation at Mars, in turn, relied for its financial success in large part on a loyal, motivated, high-performing workforce. ‘It’s not only the right thing to do morally, [looking after one’s workforce and operating in mutually beneficial ways], it’s also a good thing to do for business. You have incredible intelligence from people at all different levels of an organization and if you can really build their loyalty and motivation for the benefit of the company, then you will have a market advantage.’12

From a Research Project to a Game-Changing Innovation with Broad Application

In electing to undertake the [EoM program], Mars is positioning itself for leadership in the new scientific revolution focused on business and economics. The groundbreaking work started by the Catalyst organization has the potential for creating an enduring legacy of corporate shared value nested within an environment of competitive advantage.13

Mars External Peer Review Panel, July 2013

Catalyst launched EoM at the start of 2007 initially as an ‘evenings and weekends’14 type of research project. In subsequent years, the promising progress of the initiative would transform it from a casual project into the Catalyst raison d’être—purpose of existence.

The challenge of determining the ‘right level of profit’, Catalyst initially assessed, was one with both moral and social dimensions beyond the purely financial. Catalyst was also asked as part of the profit issue to consider two corollary questions posed by the Mars CEO and CFO regarding whether there is a relationship between profit and growth, and if there exists an optimum profit level to ensure resilience and durability over generations.

In investigating these questions, Catalyst found—based on an analysis of the performance over a forty-year period of some 3,500+ companies— no evidence at all of a relationship between past growth and future profitability, or between past profitability and future growth. The only evidence found was a relationship between past and future profitability.15 Accordingly, the corporate think tank proposed that the very definition of the prosperity Mars and other companies generate should not be confined to the narrow financial performance metrics most widely used by businesses, including Mars, but should address the holistic value created and/or destroyed and then leveraged by business across the three pillars (3Ps) of performance, people, and planet within the business ecosystems in which firms operate.

While Catalyst quietly went much deeper from a research perspective into the topic in 2007–08, the global economic crisis that began in October 2008 generated intense discussion across the world16 about whether the Friedman ‘Chicago School’ model of financial capitalism favouring shareholder returns at the expense of all other stakeholders had run its course and had become systemically dysfunctional. Such debate gave Catalyst’s nascent new business model research programme important forward momentum in parts of Mars17 that, in turn, led to formalizing the approach as a series of experimental business pilots across different Mars segments that are continuing and multiplying in number today.

Piloting EoM in Mars

The 24-month long Mars Drinks (coffee) EoM pilot concluded at the end of 2011. It was divided into a number of work streams covering performance (shared financial capital), people (human and social capital), and planet (natural capital) across the entire coffee value chain, from farmer to consumer. This project is discussed in more detail in Chapter 10.18

The Catalyst team, with its Mars Drinks and external academic partners, found that human, social, natural, and shared financial capital could in fact be measured with enough simplicity for business to make use of them; with sufficient robustness and uniformity across different cultures, markets; and on both the demand and supply sides of the company. The findings of the pilot proved to be foundational for the EoM pilots that followed, and in 2011, the external co-chair of the Mars Science Advisory Council was asked to lead what became an extensive nine-month external peer review of whole initiative.

The first external peer review panel included seasoned leaders from business, academia, and non-governmental organizations. It completed its work in 2012 and issued a report to Catalyst and the Mars leadership in July 2013 strongly endorsing both the science underpinning EoM and the potential for application to business.19 A further internal Mars review of the initiative was conducted soon after, noting inter alia that the Catalyst team’s human capital work ‘provided a substantial amount of insight which will be used [at Mars] in developing this overall strategic lever, [and the team] unearthed a very significant new insight that shows a strong correlation between social capital [and] the productivity and ability of communities to develop’.20 Armed with the encouraging findings of the distinguished external peer review panel and with sufficient support from those senior executives involved in the internal Mars senior leaders review that followed, Catalyst was able to launch its next pilots, expanding the programme to different parts of the Mars ecosystem.

The Ivorian EoM Cocoa Pilots (2012–13/2014–15)

In 2012–13, then again in 2014–15, Catalyst conducted two field pilots to identify and measure social capital in a number of cocoa farming communities in Ivory Coast, where the largest proportion of the world’s cocoa is grown. The outcome of these pilots confirmed the pattern in cocoa discovered across the related pilots in coffee of the same three variables—simplified here as trust, social cohesion, and capacity for collective action—together accounting for over 80 per cent of what constitutes social capital in a given community, and in yet another geography that had a distinctively different cultural context than the previous piloting work. Moreover, the research team achieved another breakthrough through its Ivorian pilots. From the data of the two cocoa pilots, Catalyst identified a significant correlation between the amount of social capital in a given farming community with that community’s agricultural productivity and with the farmers’ propensity for modifying their agronomic practices to improve crop yields. Catalyst, therefore, concluded that social capital (and later human capital) is a potentially critical element in any intervention aimed at increasing output along with sustaining quality-of-life enhancements.21

The Wrigley Kenya Pilot (2012–13)

Building on what was learned in prior EoM pilots in Mars Drinks, and as the first Ivorian cocoa exploratory pilot was underway, the Mars Wrigley Kenya pilot was launched in 2012 following a Catalyst–Wrigley workshop in Zurich, Switzerland.22 It was the first attempt to introduce some of EoM’s non-monetized metrics (human and social capital) as key performance indicators (KPIs) and new management practices to create a new type of route-to-market business for a Mars segment—in this instance, Mars Wrigley in East Africa where Wrigley’s only African chewing gum factory was located. The Mars leadership identified a key motive and objective for this pilot as: ‘Aspiring to make a difference to People and Planet through our Performance. As we build and grow the business the [Mars Wrigley] segment will also take steps to firstly aid decisions and measure impact using the learning from the PIA [Principles-in-Action] metrics [aka EoM] pilots.’23

The Kenya pilot initially comprised five independent but interrelated workstreams covering the Kenyan market. The most important of the workstreams, which soon subsumed the others, became what is called ‘Maua’.24 Today Maua is a profitable, fast-growing, socially oriented micro-distribution business for Wrigley chewing gum operating in the slums outside Nairobi and in some rural areas in Kenya that traditional distribution methods are unable to reach.25 Maua challenged traditional route-to-market (RTM) approaches, which typically use a master distributor rather than micro-distributors and seek to maximize profit for shareholders rather than to address stakeholder needs as the means to the end of a healthy business. In many ways, Maua was a true business breakthrough for EoM and for the sponsoring Mars business segment, demonstrating how by using non-traditional (non-financial) KPIs that put the interest of stakeholders ahead of maximizing profit for shareholders, highly performing businesses that are both scalable and deliver measurable social value are possible.26

Catalyst learned through Maua that by unlocking a successful and sustainable RTM, the construction of a business ecosystem that addresses the needs of individuals, their communities, and the need for partnering with new, non-traditional (for business) institutions is required. It also necessitated a rethink of the traditional metrics, incentives, and accountability systems used to support, measure, and reward long-term success.

In June 2018, the Mars Wrigley segment took the decision to globally scale up Maua, taking full ownership and investing further in growth of existing Maua programmes in Kenya and the Philippines that started as Catalyst pilots in 2013 and 2014, respectively, as well as initiating a plan to expand Maua into Tanzania, Egypt, Nigeria, India, and China.27

Partnership with Oxford University

In June 2014, Mars Catalyst entered a five-year joint research partnership with Oxford University’s Saïd Business School called the Mutuality in Business (MiB) programme.28 The aim of the hybrid arrangement, which began its fifth year on 1 October 2018, has been to further advance EoM research and to begin to build a global movement around this approach to making business more responsible in ways that are measurable, profitable, and scalable, unlike the typical corporate social responsibility programme, the vast majority of which do none of these things, however beneficial they may be at a local level.

Conclusion

The story of EoM in many ways is in fact currently at the ‘end of the beginning’, but with a still very long way ahead . . .

As this book is being assembled, the two largest Mars business segments—Mars Petcare and Mars Wrigley—have sponsored multiple new EoM pilots to test the approach in different market and segment situations:

The Maua micro-distribution route-to-market approach, powered by EoM, is, as was noted earlier, being globally expanded by Mars to countries in Africa, South and East Asia.

The Maua approach is being further tested by Catalyst in India as a way to bring a new Mars affordable nutrition product to market to provide, in addition to good job opportunities, a health and wellness benefit.

In China, an EoM pilot on human capital across multiple Mars segments identified the true drivers of well-being among the entire Mars workforce there and several other new EoM China pilots have just been commissioned and will soon be scoped.

In Ivory Coast, where a great deal of the world’s cocoa is grown, yet farmers continue to suffer severe impoverishment, the newly created Mars Cocoa Enterprise is now partnering with Catalyst to explore how EoM approaches can be applied to help mitigate farmer poverty, while helping to secure the cocoa supply chain. The fast-growing premium petfood business, Royal Canin, has sponsored a pilot in the very mature market of Europe as has the Mars Pet Nutrition Poland business.

The Mars Veterinary Healthcare business is now sponsoring new EoM pilots, including the first EoM foray into North America.

A new EoM ‘mutual profit P&L’ single bottom line accounting approach is now ready for practical business testing, including for how such an expanded P&L alters manager behaviour.29

At the time of this writing, Catalyst is in the midst of its first EoM pilot for a non-Mars company—a global retail conglomerate based in Europe—to explore new business ecosystems and to share EoM learnings that can be seeded in this way into another sector of the economy, yielding new learnings to advance the approach.

Putting Purpose into Practice at Mars

By Grant Reid, president and chief executive officer, Mars, Incorporated

Over the last few years at Mars we’ve invested a good bit of time and energy considering what it is that distinguishes us as a private, family business. In today’s world, it is more important than ever to be able to articulate what you stand for. It’s important to our associates (we don’t use the word employees), consumers, customers, and the public. The outcome of this self-reflection, as well as conversations with our stakeholders about what’s unique about Mars, is our purpose statement: ‘The world we want tomorrow starts with how we do business today.’ This simple, powerful articulation connects our history as a family-owned company guided by five principles (quality, responsibility, mutuality, efficiency, freedom) to the future we want for ourselves and the world. It’s more than a tagline. It is supported by a commitment to measure our performance against our purpose on multiple dimensions. The Mars family is holding the Mars board of directors and leadership accountable for delivering across multiple dimensions including financial performance metrics, our positive societal impact and the trust we earn with our stakeholders.

For us, profit without purpose isn’t meaningful. Equally, purpose without profit isn’t possible. Our belief is that business can and should make the world a better place while delivering superior business performance. We’re not alone, research indicates that purpose-oriented companies outperform the average. For Mars, business has never been a zero-sum game where one can only win if someone else is losing. On the contrary, we have sought to create enduring, shared value for Mars and our stakeholders—this is the very definition of our ‘mutuality’ principle first described by Forrest Mars, Snr. in 1947. The challenges the world faces today are different than those in the post-world-war 1940s, but they are just as daunting. Poverty, water stress, climate change, human rights abuses, and other societal and environmental issues are holding back the potential of people, communities, and business. Business absolutely has a role and a responsibility in addressing these challenges—because it is the right thing to do—and because business can’t hope to prosper in an environment where society and the planet, upon which we all depend, are not.

The Economics of Mutuality is a powerful concept that reflects the value for society and the environment can be created (or compromised) based on how a business operates, and that business needs non-financial forms of capital (human, social, natural) as much as it needs financial capital to operate. There are a number of case studies outlined in greater detail in this chapter that help bring this to life. For example, EoM-inspired business models like the ‘Maua’ micro-distribution route-to-market business discussed later in this book, is helping Mars deliver quality growth in emerging geographies and hard-to-reach communities, while creating enduring opportunity within those communities.

Business management requires making choices about how to leverage finite resources for maximum impact. By providing meaningful measures of non-financial forms of value to supplement traditional financial capital measures, business can help equip managers with a fuller set of data points. This, in turn, can change the conversation on return on investment and make clearer the interdependencies between these forms of capital and the impact that they have on resilient business performance.

In today’s world, the workforce and the general public are looking to business to lead, not just as drivers of economic growth, but as institutions that are helping the world address its challenges. Reinventing management practices to take a holistic view of profit and purpose will help us live up to these expectations while creating enduring business benefits. I’m excited about the future this can create for Mars and business at large.

The future for EoM looks bright, and Mars has to date viewed learning from the programme not as intellectual property, but rather as intellectual capital to be shared openly with similarly purposed organizations. In many ways Catalyst sees EoM as a non-rival good, in that Mars (and others who adopt the approach) will gain more by sharing it than by keeping it to themselves. The next step of the journey, therefore, will be partnering in an open collaborative space starting in January 2019, and this will be discussed elsewhere in this book.

Notes

Extracted from the Mars Personnel Manual, Mars Slough UK Site, 1947, Mars Museum, McLean, Virginia.

‘The Objective of the Company’, letter by Forrest Mars, Snr., 1947, Mars family archives.

Five Principles of Mars, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7PniaEqe478.

Mars, Incorporated refers to its employees as ‘associates’ to emphasize the personal stake each employee has in the success of the enterprise.

‘The Sweet Secret World of Forrest Mars’, Fortune Magazine, 1967.

John Mars comments in conversation about his 2006 ‘right level of profit’ question with Frank Akers, chairman, Mars Science Advisory Council, 2012.

The Catalyst emphasis on the need to address management incentives began at the very start of the EoM programme with the exploration of new non-financial forms of capital, but was codified more recently in 2017–18 through work partnering with Oxford University on introducing non-financial metrics into the P&L of piloting business units to turn what was heretofore a purely financial P&L into a ‘mutual P&L’. This work is ongoing and is covered in depth elsewhere in this book.

‘The Economics of Mutuality Explained’, internal Mars Catalyst briefing paper drafted by Jay Jakub, Alastair Colin-Jones, Francois Laurent, and Bruno Roche et al. for senior Mars managers, Spring 2018.

Schein (2010).

‘The Purpose of the Company’, letter by Forrest Mars, Snr., 1947, Mars family archives.

‘Quakers are members of the Religious Society of Friends, a faith that emerged as a new Christian denomination in England during [the] mid-1600’s and is practiced today in a variety of forms around the world...[Quakers practice] testimonies of pacifism, social equality, integrity, and simplicity . . . Today, many [Quakers] include stewardship of [the] planet as one of [these] testimonies.’ Extracted from the Quaker Information Center, http://www.quakerinfo.org/ index.

Ibid,p.21,quotingPeterHolbrook,chiefexecutiveofSocialEnterpriseUK,inan interview with Tom Woodin.

MarsEconomicsofMutuality/Principles-in-ActionMetricsExternalPeerReview Summary report, internal Mars document delivered by Frank Akers, July 2013.

Frequent observation of Mars chief economist and Catalyst managing director Bruno Roche, as conveyed to the author.

Internal Mars Catalyst analysis using Baysian classifier algorithmic and other techniques of data from 3,500+ public and private companies with revenues of > $1bn spanning four decades, S&P, 2007.

Whiletherewerehundredsofnewsstoriesworldwidequestioningtheviabilityof the financial capitalism model in the months immediately following the October 2008 economic meltdown, it is notable that this intense debate extended into what were widely recognized as the media bastions of the Friedman model, such as the Financial Times, which later launched a series called ‘The Future of Capitalism.’

Theloudpublicdiscourseinlate2008,early2009aboutthefutureviabilityofthe financial capitalism approach in its present form prompted some of the harshest critics at Mars of the multi-capital approach being explored by Catalyst to withdraw or otherwise quiet their objections, allowing for EoM to be formally brought to the attention of the Mars Leadership Team and members of the Mars family in an internal Mars symposium in April 2009 at the firm’s global headquarters in McLean, Virginia. This symposium prompted the Mars Drinks and Mars Food presidents to volunteer to host the first EoM pilot, with Mars Drinks being selected, mostly on the basis of its very small size, the limited ability of Catalyst’s small team to run multiple pilots simultaneously while continuing the work of its Marketing and Culture Laboratories, and the shared passion of the Drinks Leadership Team for the topic. It is noteworthy that members of that Drinks Leadership Team from 2009 today include the executive vice president of Mars who services also as the Mars Wrigley Confectionery president (Martin Radvan); the president of Mars Global Services (Angela Mangipane); and the CFO of Mars Petcare—the company’s largest segment (Jacek Szarzynski). And the current global vice president for corporate affairs at Mars, Andy Pharoah, was the overall Wrigley coordinator of the first experimental EoM RTM pilot in Africa while serving as head of corporate affairs for the Wrigley segment.

Further details can also be found in Roche and Jakub (2017).

Mars Economics of Mutuality/Principles-in-Action Metrics External Peer Review Summary report, internal Mars document delivered by Frank Akers,

July 2013.

‘PiA [Principles in Action, aka Economics of Mutuality] metrics conclusions and

recommended next steps’, internal Mars document drafted by Mars Science Advisory Council co-chairman Frank Akers, summarizing key findings of a high-level internal Mars review of the EoM programme on 22 October 2013. Note that this document is undated, but almost certainly was written and delivered in the week following the 22 October 2013 review in plenary if not on the day of or after that review.

Mars Economics of Mutuality/Principles-in-Action Metrics External Peer Review Summary report, internal Mars document delivered by Frank Akers, July 2013.

The author has personal knowledge of this workshop by virtue of having attended it and having helped organize it.

‘PiA [Principles in Action, aka Economics of Mutuality] metrics conclusions and recommended next steps’, internal Mars document drafted by Mars Science Advisory Council co-chairman Frank Akers, summarizing key findings of a high-level internal Mars review of the EoM programme on 22 October 2013. Note that this document is undated, but almost certainly was written and delivered in the week following the 22 October 2013 review in plenary if not on the day of or after that review.

Maua is a Swahili word meaning ‘blossoming flower’. It was suggested by one of the micro-distributors in the programme because the sales territories were flower shaped. As Maua has been replicated elsewhere and is now the subject of a Mars Wrigley Confectionery global scale-up effort, this Swahili ‘branding’ of this EoM RTM model is now the standard.

See chapter x for further details. See also the Maua case study, ‘Uncovering Hidden Riches: Project Maua Kenya—A Demand Side Business Model’, economicsofmutuality.com website. And see Roche and Jakub (2017).

See the ‘Project Maua, Kenya: A Demand Side Business Model’ case study, posted both on the website of Oxford University’s Saïd Business School (https://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk) and on the website https://eom.org. Note: Maua is also discussed in detail in Roche and Jakub (2017).

‘Economics of Mutuality, Route to Market Rollout: A Global Opportunity’, internal Mars PowerPoint deck prepared by the Mars Wrigley Global Confectionery Maua Scale Up Team with support from Mars Catalyst, June 2018.

See ‘Agreement for the Sponsorship of a Research Project’, master agreement between Mars, Incorporated and Oxford University’s Saïd School of Business, June 2014. See also ‘Heads of Terms Agreement’, specifying the joint intent of Mars and Saïd Business School to undertake a five-year partnership to advance EoM, June 2014 (executed by Stephen Badger from the Mars board of directors for Mars, Incorporated and by Peter Tufano, dean of Saïd Business School, for Oxford University).

Harvard’s Robert Eccles, widely known as the inventor of integrated accounting, is Catalyst’s main partner in this work on mutual profit, along with Oxford’s Saïd Business School through the MiB programme noted earlier.

Jay Jakub is part of the Mars, Inc. think tank ‘Catalyst’—created in the 1960s by Forrest Mars, Sr. to challenge conventional business thinking and to develop breakthrough capabilities for the firm. Born in Rahway, New Jersey—ironically the hometown of Milton Friedman, financial capitalism’s founding father—Jay is the senior director for external research and co-manages the Economics of Mutuality initiative. Married to Eleni (Xanthakos) and father of two teenagers, Jay’s doctorate is from St. John’s College, Oxford University, and he is the co-author of Completing Capitalism (Berrett-Koehler, 2017 and CITIC Press in Mandarin, 2018) and author of Spies and Saboteurs (Macmillan and St. Martin’s Press, 1999).

Bread and Honey:

Social Flourishing, Mutuality,

and Economics

By Martyn Percy

The Meaning of Mutuality

By Catherine Dolan, Bojan Angelov,

and Paul Gilbert

Published by Oxford University Press. Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom.

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark ofOxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Oxford University Press 2021. The moral rights of the author have been asserted. First Edition published in 2021. Impression: 1.

Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization.

This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of this licence should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication. DataData available. Library of Congress Control Number: 0000000000. ISBN 978–0–19–887070–8. DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198870708.001.0001.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.