Introduction

Established in 1863, Solvay is a global chemical company with its headquarters in Belgium. It employs approximately twenty-five thousand people and operates in sixty-one countries. Revenues in 2017 were €10.1 billion.1 As part of its stated organizational mission, Solvay is ‘committed to developing chemistry that address[es] key societal challenges’.2 To this end, Solvay produces a range of chemical products with applications in health, agriculture, electronics, aerospace, and automotive, industrial, and consumer goods.3 The company was founded as a family business, and family members continue to control 80 per cent of the shares of the publicly traded holding company, Solvac. With control of 30 per cent of Solvay shares, Solvac is the main shareholder in Solvay.4

In recent years, Solvay has increased its focus on products that provide sustainable solutions. Simply put, Solvay has begun asking fundamental questions about its own impact and ability to continue creating value into the future. Solvay’s line of questioning initiated a process of redefining value creation, moving the company towards a long-term strategy of considering how non-financial, or in Solvay’s term, ‘extra-financial’, forms of capital affect the business. How, Solvay asks, can the company do more good and at the same time do less bad? Solvay aims in this way to maximize its sustainability practices and minimize its negative environmental impact. By ‘asking more from chemistry’, Solvay aims to create sustainable solutions and strategies that will carry the company into the future.5

In examining Solvay’s mutual business strategy, this case study focuses in particular on the company’s Sustainable Portfolio Management (SPM) tool, which provides a means of identifying, planning, and operationalizing sustainable business strategies. As the annual report from 2016 states, Solvay takes financial and extra-financial criteria into consideration in operational management and strategy decisions.6 This initiative helps integrate sustainability strategies holistically into Solvay’s strategic decision-making.

Pain Points in the Ecosystem

Aligning with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Solvay is a supporter of sustainability in its daily operations and long-term strategy. It defines sustainable solutions as having ‘direct, significant, and measurable social and/or environmental impacts’.7 Meeting existing (and anticipating future) sustainability challenges has become a key priority for Solvay. Recognizing sustainability as integral rather than secondary to assessing its profit and loss, Solvay has committed to developing its Sustainable Portfolio Management tool and other means of improving product sustainability and performance.

These issues have particular salience for chemical companies looking to remain competitive in the future. Recent industry analysis suggests that the chemicals sector faces a number of critical structural challenges. According to a report by global accountancy firm PwC, demand for chemicals has fallen, with industry sales growth increasing only an ‘anaemic’ 2.1 per cent in 2016 as the sector faced declining industrial production and ‘broad inventory rightsizing by many of its customers’.8 With growth in the sector appearing unlikely in the coming years, the report authors urged chemical companies to explore strategies that may lead to profitable growth, such as ‘value capture, digitization, and smarter portfolio management’.9 Moreover, across the sector, there is a growing recognition that ‘structural weakness in most markets and recycling and reuse, which impact the sale of virgin materials, are combining to substantially reduce demand’.10 Faced with these challenges, chemical companies are seeking new strategies to keep their businesses competitive in the future.

New approaches, additionally, must acknowledge and take into account the finite nature of the earth’s natural resources. For a chemical company, these sustainability considerations carry particular weight. As a result, gaining market share is likely to prove a crucial challenge in the coming years.11 Future opportunities within this sector are likely to result from developing substantively different strategies from those that were effective previously. The reciprocal nature and interdependency of financial and non-financial forms of capital rest at the core of this new approach.

Solvay, accordingly, has taken a life-cycle approach to its products, looking for ways to ensure that the business is ready to tackle what it describes as the ‘planetary issue of resource scarcity’.12 By identifying and potentially getting ahead of challenges within its product ecosystem, Solvay aims to ensure the sustainability of both the earth’s natural resources and its own business. Through ‘anticipation, innovation, and agility’, Solvay aims to foresee and respond to challenges down the line.

Business Strategy

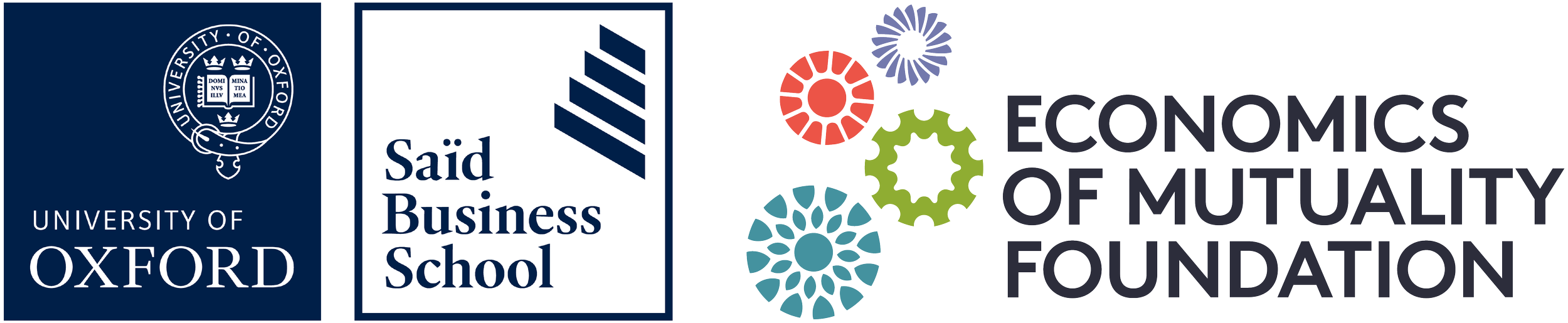

Confronting challenges within the chemicals sector necessitates not only a change in mindset, but also a new set of skills and tools. Solvay’s management aims to tackle these challenges through internal innovation. The company developed its SPM tool to help assess and map its products’ strengths and weaknesses (see Figure 26.1). The tool aims to guide the company towards creating products that both provide sustainable solutions in the marketplace and reduce environmental and social risks for the company.

The tool maps all products according to their environment manufacturing footprint and its correlated risks and opportunities. It uses a cradle-to-gate life-cycle assessment, quantifying environmental footprints and using costs, which reflect the cost to society. The total cost to society is then compared to the price of the product. These factors, specifically, help assess operations’ vulnerability.

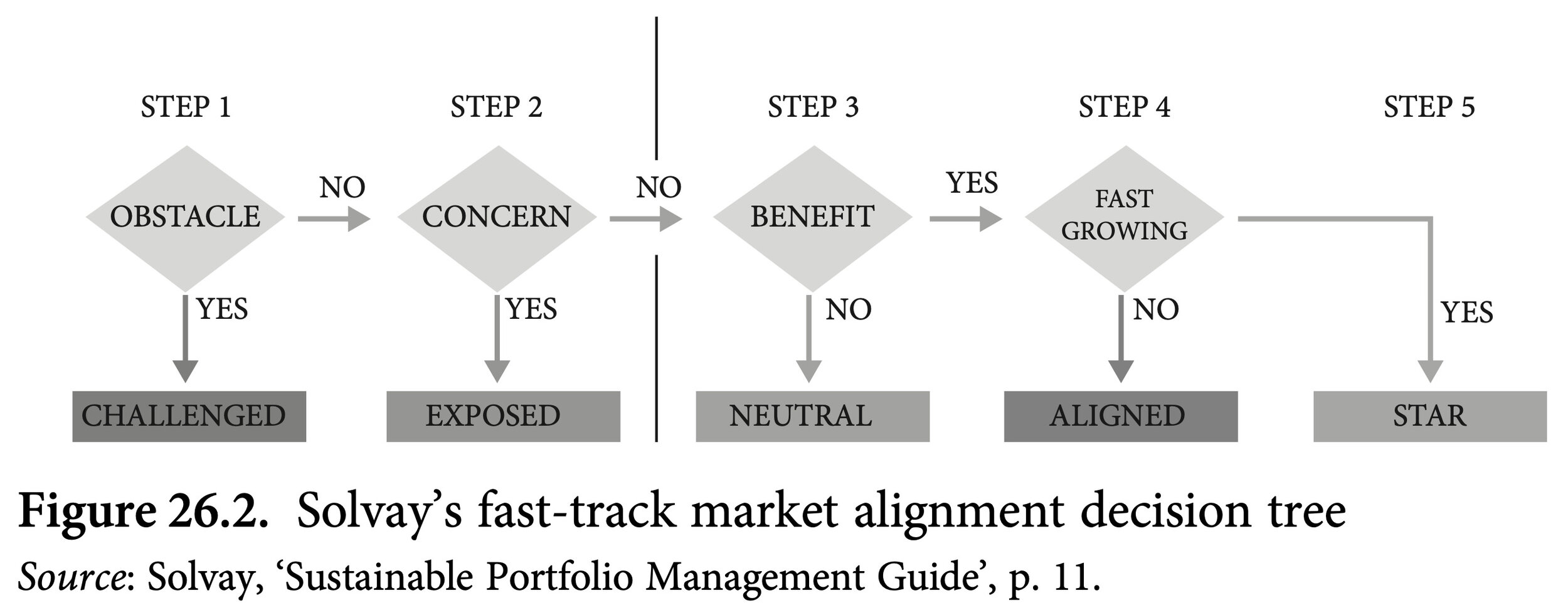

This is then set against the ways in which a product brings ‘benefits or faces challenges in a market perspective’.13 These measures focus especially on market alignment, helping to identify the extent to which ‘one product in a given application is part of the sustainable development solution or part of the problem from a consumer and market perspective’.14 It uses a questionnaire, based on a qualitative, evidence-based collection of sustainability-related market signals. All the sustainability signals assessed using the questionnaire are run through a decision tree. This defines the exact positioning of the product-application combination, or, PAC (see Figure 26.2).

First Solvay looks at obstacles and concerns. Any obstacle identified will immediately rank the PAC as challenged and anything raising concern as exposed. Solvay then considers the positive signals. If Solvay finds no negative and no particularly positive impacts, the PAC is categorized as neutral. If the PAC analysed demonstrates a direct, significant, and measurable benefit to the market, which has a positive impact on at least one of the sustainability benefits assessed, it is listed as aligned. If, in addition, Solvay registers double-digit growth potential in sales forecasts, the PAC is categorized as star.15

SPM gives Solvay a means of assessing the risk profiles of its products and making strategic decisions accordingly. Solvay’s sustainable development function manages the SPM methodology. Solvay deploys SPM in close cooperation with its business units and functions in key processes: strategy, research and innovation; capital expenditures; marketing and sales; and mergers and acquisitions. The SPM methodology is part of the Solvay Way framework and helps measure how well global business units and corporate functions have integrated sustainability into their business practices.16

Significantly, the SPM profile is an integral part of the strategic discussions between global business units and the Executive Committee. Mergers and acquisition projects are also evaluated using SPM to see if the investment is feasible in the light of sustainable portfolio targets. Investment decisions (capital expenditure above €10 million and acquisitions) made by the Executive Committee or the Board of Directors include a sustainability challenge that encompasses an exhaustive SPM analysis of the potential investment. All research and innovation projects are evaluated using SPM. Finally, in marketing and sales, SPM makes it possible to engage customers on fact-based sustainability topics aimed at creating value for both Solvay and the customer. These areas of mutual interest and concern include climate change action, renewable energy, recycling, and air quality.

Performance

Over the past three years, Solvay’s products have experienced greater annual revenue growth rates in areas in which customers and consumers are seeking out Solvay’s products to match their unmet social or environmental needs. More specifically, volume annual growth rate per SPM category showed that products in the solutions category grew by +3 per cent, whereas those in the challenges fell by a factor of 2 per cent. As a note, these calculations were based on sales of the same product, same application, and same SPM ranking over the last three years, representing 44 per cent of Group sales (out of which two-thirds came from volume growth).17

Prognosis

Although long-term research remains to be done, at present it appears that the SPM tool has been leading to good performance according to environmental, social, and financial metrics. Above all, SPM has become key to strategic decision-making within the company, informing merger and acquisition (M&A) strategy, decisions about investments, and improved customer engagement through marketing and sales.

Signalling its priorities, Solvay debuted its first ‘integrated’ annual report in 2016. This document differed from a traditional annual report by aiming to show the significance of non-financial or extra-financial forms of capital in furthering Solvay’s business objectives. Rather than relying exclusively on financial metrics, Solvay has factored sustainability into an assessment of the company’s overall performance. As the report demonstrates, combining various forms of capital represents a strategy that Solvay aims to showcase to the public. Financial and non-financial forms of capital combine to present a holistic picture of Solvay’s business. As Solvay looks to the future, it aims to uncover strategies that will sustain the market leadership position for its products. At the same time, and relatedly, Solvay also aims to create sustainable strategies that will benefit the planet and help advance its business goals. By addressing the negative externalities within its ecosystem, Solvay aims to create a series of sustainable practices that will ensure the long-term viability and growth of its business.

___

Notes

‘Annual Integrated Report 2017’, Solvay.

‘Home’, Solvay, Solvay.com, https://www.solvay.com/en/index.html.

‘Annual Integrated Report 2016’, Solvay.

‘Annual Integrated Report 2017’, Solvay.

‘Annual Integrated Report 2016’, Solvay.

‘Annual Integrated Report 2016’, Solvay.

‘Annual Integrated Report 2016’, Solvay.

Bebiak et al. (2017: 3).

Bebiak et al. (2017: 11).

Bebiak et al. (2017: 8).

Bebiak et al. (2017: 8).

‘Solvay’, Ellen MacArthur Foundation, https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/about/partners/global/solvay.

‘Sustainable Portfolio Management Guide: Driving Long-Term Sustainable Growth’, Solvay, 4, https://www.solvay.com/sites/g/files/srpend221/files/2018-07/Solvay-SPM-Guide.pdf.

‘Sustainable Portfolio Management Guide: Driving Long-Term Sustainable Growth,’ Solvay, 7.

‘Sustainable Portfolio Management Guide,’ Solvay, 10.

‘Annual Integrated Report 2017’, Solvay, http://annualreports.solvay.com/2017/en/extra-financial-statements/sustainability-management/sustainable-portfolio-management.html.

‘Annual Integrated Report 2017,’ Solvay, http://annualreports.solvay.com/2017/en/extra-financial-statements/business-model-and-innovation/sustainable-business-solutions.html#accordion2.

Case Study Contributors

Justine Esta Ellis, University of Oxford

Alastair Colin-Jones, Mars Catalyst

Jean-Marie Solvay, Solvay Chemical

Michel Washer, Solvay Chemical

Interface: Turning an Environmental Problem into

a Business Opportunity

By Jon Khoo, Miriam Turner,

and Justine Esta Ellis

Z Zurich Foundation:

Building the Case for Effective Insurance in Flood-Prone Areas

By Helen Campbell Pickford, David Nash, and Justine Esta Ellis

Published by Oxford University Press. Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom.

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark ofOxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© Oxford University Press 2021. The moral rights of the author have been asserted. First Edition published in 2021. Impression: 1.

Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization.

This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution–Non Commercial–No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of this licence should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication. DataData available. Library of Congress Control Number: 0000000000. ISBN 978–0–19–887070–8. DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198870708.001.0001.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.